Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic systemic autoimmune inflammatory disease primarily affecting synovial joints, causing inflammation, pain and stiffness.

In this blog we will delve into the epidemiology, aetiology, pathology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis.

Table of contents

Epidemiology

Rheumatoid arthritis is a relatively common chronic autoimmune disease affecting approximately 1% of the population worldwide. Prevalence varies by region, with higher rates being observed in developed countries. Women are affected more than men with a female-to-male ratio of 3:1. RA can occur at any age but has a peak prevalence between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

Aetiology and risk factors

The aetiology of RA is unknown but is believed to be multifactorial involving a complex interplay of genetic, environmental and immune factors.

-

- Gender: Women are affected three times more frequently than men before menopause with the sex incidence being equal thereafter, indicating a potential role for female sex hormones

-

- Familial: Incidence is higher in patients with a family history of rheumatoid arthritis

-

- Genetics: Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) -DR4 and DRB1 confer susceptibility to RA and are associated with more severe disease.

-

- Cigarette smoking is associated with higher risk for and severity of RA

-

- Obesity

Pathology

RA is characterised by chronic inflammation of the synovium associated with infiltration by inflammatory cells and generation of new synovial blood vessels. The thickened synovium grows out over the surface of cartilage, in the form of a pannus. Pannus is a tumour-like mass that destroys the articular cartilage and subchondral bone, causing bone erosions.

The triggering antigen in RA is not known but inflammatory mediators produced by activated T cells, macrophages, mast cells and fibroblasts such as interleukins, interferon and TNF-alpha contribute to the ongoing synovial inflammation. Local production of rheumatoid factor* by B cells and formation of immune complexes with complement activation also maintain chronic inflammation

Clinical presentation

-

- Typical presentation is with insidious onset of joint pain, swelling and stiffness.

-

- RA characteristically involves small joints

-

- Joint involvement is symmetrical most often affecting the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints of the hands, wrists, hips, knees and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints of the feet, sparing the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints

-

- Most patients eventually have multiple joint involvement

-

- As the disease progresses joint instability and deformity results from weakening of the joint capsules

-

- Uncommon presentations are:

-

- 1. Abrupt onset of widespread arthritis (‘explosive’)

-

- 2. Monoarthritis of different large joints in a relapsing and remitting pattern (‘palindromic’)

-

- 3. With a systemic illness associated with fatigue, malaise and weight loss with few joint symptoms at the outset

-

- 4. With extra-articular complications

-

- Uncommon presentations are:

Typical deformities in the hands:

-

- Swan Neck Deformity: Characterized by hyperextension of the PIP joint and flexion of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint.

-

- Boutonniere Deformity: Characterized by flexion of the PIP joint and hyperextension of the DIP joint.

-

- MCPJ’s: Swelling of metacarpophalangeal joints

-

- Ulnar Deviation: Fingers may drift towards the little finger side of the hand due to joint and tendon damage.

-

- Z-shaped Thumb: Also known as a “Z deformity,” where the thumb flexes at the MCP joint and hyperextends at the interphalangeal joint.

-

- Radial deviation of the wrist

Extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis

Extra-articular complications occur in 30% of patients. The following are some of the extra-articular manifestations of RA

-

- Systemic: fever, fatigue, weight loss, malaise

-

- Rheumatoid nodules: occur in ~20% of patients with long-standing disease. Subcutaneous nodules usually occur over pressure points of the fingers, elbows and Achilles tendon but nodules can occur in the pleura, lung and pericardium

-

- Ocular: scleritis, episcleritis, scleromalacia perforans, keratoconjunctivitis sicca

-

- Haematological: anaemia, lymphadenopathy, leukopenia, thrombocytosis, Felty’s syndrome (RA, neutropenia and splenomegaly)

-

- Cardiac and peripheral blood vessels: pericardial effusion, pericarditis, valvular heart disease, vasculitis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, accelerated atherosclerosis and increased cardiovascular risk

-

- Respiratory: pleurisy, pleural thickening, pleural effusions, interstitial lung disease, lung nodules, obliterative bronchiectasis, Caplan’s syndrome (pneumoconiosis with rheumatoid nodules in the lungs)

-

- Renal: glomerulonephritis, drug-induced nephropathy, secondary (AA) amyloidosis

-

- Neurological: Entrapment neuropathy (e.g. carpal tunnel syndrome), peripheral neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, cervical myelopathy particularly due to atlanto-axial subluxation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of RA involves a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory tests and imaging studies.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has established criteria for diagnosis, which include the presence of joint swelling, joint tenderness, elevated acute phase reactants ( CRP, ESR), the presence of rheumatoid factor or anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and duration of symptoms. ACR criteria standardise the diagnosis of RA and guide treatment decisions with a score of 6 or more required for diagnosis of RA

Laboratory

-

- Full blood count: anaemia is common, thrombocytosis

-

- Inflammatory markers: ESR and CRP are usually elevated reflecting the inflammatory process

-

- Auto-antibodies: Rheumatoid (Rh) factor is positive in 70% of cases; however Rh factor lacks specificity being found in other autoimmune diseases and some infections. Anti-citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP) has higher sensitivity (90%) and specificity (80%) than rheumatoid factor. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) is raised in 30% of patients.

-

- Liver, renal, and bone chemistry to exclude other causes and as baseline tests prior to initiating pharmacological treatments.

-

- Synovial fluid analysis: joint aspiration is performed only if there is diagnostic uncertainty or to exclude septic arthritis. Typical findings in RA is an elevated neutrophil count

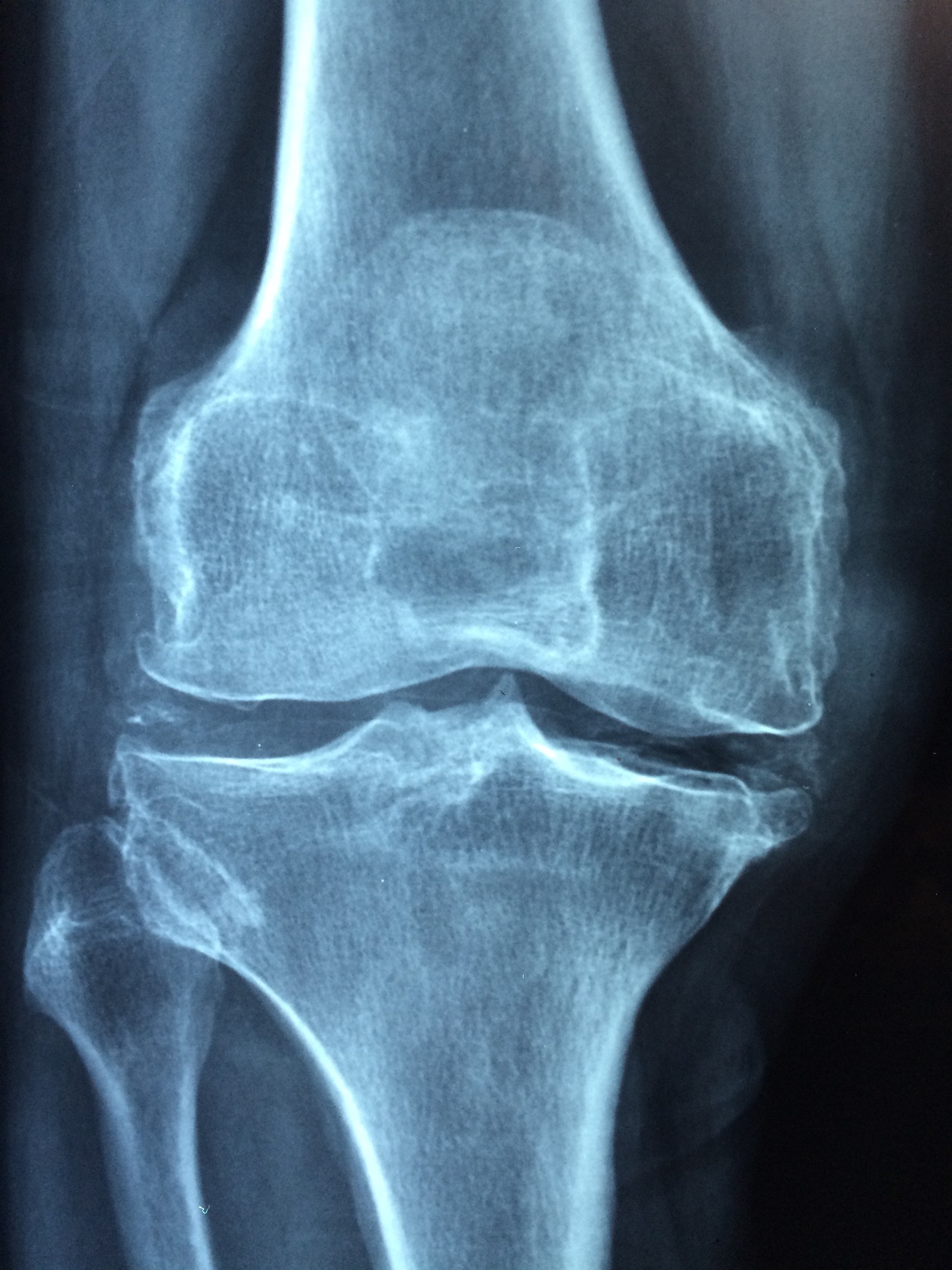

Radiological imaging

-

- Plain x-ray: is the first line radiological investigation in the diagnosis of RA. Typical findings are soft tissue swelling and in established disease joint narrowing and erosions, periarticular osteoporosis and deformity

-

- Joint ultrasound may demonstrate features of joint inflammation or joint erosion

-

- MRI is indicated where the above are nondiagnostic

Management

Management of rheumatoid arthritis involves pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. A multidisciplinary team approach involving general practitioner, rheumatology, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, chiropody, podiatry and pharmacist is essential.

Pharmacological treatments

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s) and other analgesics

NSAID’s such as ibuprofen and naproxen are effective in the management of pain and stiffness but have no effect on disease process. Several different drugs may need to be tried before finding a suitable agent as individual patient responses vary. Other analgesics include paracetamol with or without codeine

Corticosteroids

-

- Oral steroids are used early after diagnosis or during a disease exacerbation for rapid symptom control and to suppress disease activity. High doses are often required with the concomitant risk of corticosteroid toxicity; hence they are only for short-term use and at the lowest possible dose.

-

- Intra-articular injection of a long-acting steroid into a single joint may be used

-

- Intramuscular depot methylprednisolone may used to control severe flare-ups of RA

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

There are 2 groups of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD’s) – synthetic and biologic. They act mainly through inhibition of inflammatory cytokines and are used early to reduce inflammation and slow progression of disease. A combination of 4 agents may be used to induce remission when the number of agents can be reduced.

Monitoring of symptoms and bloods (particularly FBC and liver biochemistry) is required. Screening for tuberculosis is also required in high risk patients due to the immunosuppressant effects of DMARD’s.

Synthetic DMARD’s

-

- Methotrexate: up to 25mg orally once weekly. Methotrexate is a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and has additional inhibitory actions on the function of B and T cells in RA. It is first-line in the treatment of RA and considered the anchor drug. To avoid folic acid deficiency methotrexate is always prescribed with folic acid. It is contra-indicated in pregnancy due to teratogenicity and should not be prescribed in men or women in the 3 months prior to conception. Side effects include mouth ulcers, liver and pulmonary fibrosis and renal impairment

-

- Sulfasalazine: Ig orally twice daily. Side effects include mouth ulcers, hepatitis and reversible male infertility

-

- Leflunomide: 10-20mg orally daily. Side effects include diarrhoea, hepatitis, alopecia and hypertension

-

- Hydroxychloroquine: 200-400mg daily. May be used alone in mild disease but is more commonly used as an adjunct to other DMARD’s. Irreversible retinopathy is a risk with increasing dose and duration of use; baseline ophthalmic examination is recommended within 1 year of commencement.

-

- Azathioprine, cyclosporin, penicillamine and gold salts are less used due to their toxicity

-

- JAK inhibitors such as tofacitinib are oral synthetic DMARD’s

Biologic DMARD’s

-

- Biologic DMARD’s are a heterogeneous group of recombinant proteins that work by various mechanisms:

-

- Etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab: TNF-alpha inhibitors

-

- Anakinra: IL-1 receptor blockade

-

- Tocilizumab: IL-6 receptor antibody

-

- Rituximab: Anti-CD20 causing B-cell depletion

-

- Abatacept: T-cell activation co-stimulatory blockade. Abatacept is a fusion protein that binds to CD 80 and CD86 receptors on APC, selectively blocking their interaction with CD 28 on T cells

-

- Biologic DMARD’s are a heterogeneous group of recombinant proteins that work by various mechanisms:

-

- All produce sustained symptomatic improvement and retard disease progression

-

- Biologic DMARD’s are indicated when there is evidence of high disease activity (DAS 28** > 5.1) and the patient has failed therapy with 2 DMARD’s, one of which was methotrexate (unless this was specifically contraindicated)

-

- TNF-alpha inhibitors are first-line with rituximab being used if anti-TNF therapy fails or is contraindicated

-

- Etanercept and adalimumab are administered subcutaneously; infliximab is administered by intravenous infusion

-

- Rituximab can take up to 16 weeks to reach maximum effect

Prognosis

Prognosis of RA is variable but can be altered with early diagnosis and commencement of DMARD therapy. Factors associated with a poor prognosis include:

-

- Female sex

-

- Smoking

-

- HLA-DR4

-

- Insidious onset

-

- High DAS score at presentation – prognosis is worse the higher the number of joints involved

-

- Severe disability at presentation

-

- Presence of extra-articular manifestations

-

- High inflammatory and autoantibody markers

-

- Early radiological evidence of erosion

Conclusion

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease that primarily affects the synovial membrane of small and large joints. It is associated with considerable morbidity and an increase in mortality. Although the underlying cause is unknown, genetic, environmental and immune factors play a role. Early diagnosis and treatment with DMARD’s are essential to reduce the disability associated with rheumatoid arthritis and improve outcomes.

*Autoantibodies directed against the Fc portion of immunoglobulin (Ig)

** DAS 28 refers to disease activity score in rheumatoid arthritis and number 28 refers to the 28 joints examined in the assessment

Text references

-

- Guo, Q., Wang, Y., Xu, D. et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies. Bone Res 6, 15 (2018)

-

- NICE guideline Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management

-

- Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2018; 362

-

- Qjang Guo, Yuxiang Wang, Dan Xu, Johannes Nossent, Nathan J. Pavlos and Jiake Xu Rheumatoid arthritis: pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies Bone Res. 2018; 6: 15.

-

- Pastest Essential Revision notes for MRCP. Fourth edition, Philip Kaltra